Dart and the Double Spiral

by Carol Porter McCullough

Raymond Dart identified and drew attention to the double spiral arrangement of the human musculature (Carrington and Carey 1992, 113). Dart, Australian by birth, emigrated to London after graduating from medical school in 1917. He was appointed Professor of Anatomy in Johannesburg in 1923, retaining the post until his retirement in 1958. For many years, Dart was dean of the medical school at University of Witwatersrand. Dart enjoyed a varied career, becoming famous for anthropological investigations, as well as for his work in anatomy. Dart and his family had Alexander Technique lessons with Alexander’s assistant, Irene Tasker, in 1943. Dart had a single lesson with Alexander in 1949, but maintained that Alexander influenced him for the rest of his life (Dart 1996, 26).

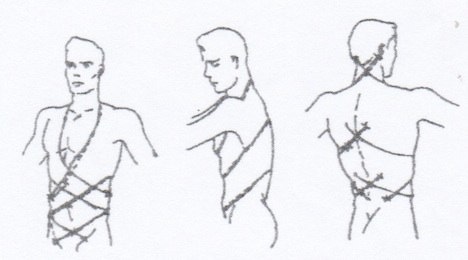

The spirals of the human musculature are mirror images of each other. Designating the right side of the pelvis as a starting point, the muscle sheet of one of the spirals travels diagonally around the side of the torso, crossing over the front mid-section to wrap diagonally upward to the left side of the torso, where the road of muscle makes a “Y,” one avenue junctioning with the muscles of the left arm, the other avenue snaking its way diagonally across the back, continuing on its diagonal journey across the neck to hook onto the head behind the ear in its original hemisphere of the right side (Dart 1996, 69), (figure 5).

The diagonal pull of these spirals of muscle accounts for the flexibility and upright capabilities of the human structure. These diagonal pulls may be likened to pulling on the bias (diagonal) of a piece of cloth. There is much greater flexibility in the cloth when pulled on the bias than when stretched on the cross grains (vertical and horizontal grains). The effect of an individual lengthening and widening his back is to activate the anti-gravity muscles (extensors) by causing a greater stretch on them. The Alexander Technique, mistakenly called a “relaxation” technique by some, is not about relaxation at all.

The Double Spiral

The pelvis and the head are connected not only by the bony, vertical structure of the spinal column, but also by the winding diagonal ribbons of muscles that make up the voluntary musculature of the torso. It is because this musculature is under voluntary control by the human nervous system that difficulties arise in an individual’s use, and consequently, potential exists for improvements in an individual’s use. Voluntary control should not be confused with conscious control. It is the unconscious control of voluntary musculature that gets one in trouble. By definition, voluntary muscles have the potential for being under the control of the individual. For an individual to have voluntary control of his voluntary musculature, he must be conscious of how he is using it. The essence of the Alexander Technique is learning to exercise conscious control of the voluntary musculature.

Anatomists have traditionally divided musculature into various muscle groups. This is useful for identification purposes but not useful for understanding the working whole of human movement. Because of the large “sheets” of muscles that form spirals around the human torso, the simple act of raising the arm to place the bow on the string cannot be made without involving the muscles of pelvis. The act of turning the head and placing it on the violin affects the musculature in the lower back, conversely, the muscular condition of the lower back affects the act of placing the head on the violin.

Support of the violin with the head involves both sets of spirals and the support of the whole back. It is when violin support is taught as a localized task of the head and shoulder that holding the violin becomes a “posture.” When the spiraling action of the human musculature during movement is considered, from the smallest movement of putting a finger down on the string, to a larger movement of shifting, to even larger movements of using the whole bow, any action involved with playing becomes an affair of the entire torso and total body.

String players traditionally speak of left hand and right hand technique as if they were entirely separate entitities. When an understanding is gained of the spiral arrangement of the musculature, such terms should become only a means of designating the specifics of the tasks each hand performs. The hands themselves are the ends of a unified process that involves the brain and entire human structure of the player.

Percival Hodgson, in his 1934 study Motion Study and Violin Bowing, made the discovery that bowing motions themselves describe arcs and spirals. Through the use cyclegraphs (“a photographic record of the track covered by a moving object”), Hodgson was able to photograph the bowing paths of artist players (Hodgson 1958, 58).

Dart himself believed in “the universality of spiral movement."

I recalled an elderly otologist named Miller, 30 years ago in New York City, demonstrating by means of examples ranging from the spiral nebulae to the human cochlea, and from the propagation of sound to the propulsion of solid bodies, that all things move spirally and that all growth is helical.(Dart 1996, 57).

Copyright 1996 Carol Porter McCullough

Reprinted courtesy of Carol Porter McCullough

About the Author

Carol Porter McCullough held advanced music degrees from Florida State University and Arizona State University where she studied viola with William Magers. She was on the music faculty for five years at Illinois Wesleyan University, where she taught viola and was Director of the String Preparatory Department. She played in numerous orchestras, including the Grand Rapids, Kalamazoo, and Peoria Symphonies, the Arizona Opera Company and Sinfonia da Camera in Urbana, Illinois. She participated in music festivals across the U.S., including the Luzerne Center for Music, where she was a member of the Luzerne Chamber Players. Carol was a certified teacher of the Alexander Technique, completing her training with Joan and Alex Murray. She conducted workshops for the Alexander Technique for string players, musicians in general and other performing artists.

For more information about Carol McCullough's work, contact: Brian McCullough.

References

Alexander, F. Matthias. 1995. Articles and Lectures. Ed. Jean M. O. Fischer. London: Mouritz.

Alexander, F. Matthias 1932. Reprint. The Use of the Self. Los Angeles: Centerline Press. Original edition, New York: E. P.Dutton & Co., Inc.

Carrington, Walter, and Sean Carey. 1992. Explaining the Alexander Technique: The Writings of F. Matthias Alexander. London: The Sheildrake Press.

Dart, Raymond A., 1996. Skill and Poise. Ed. Alexander Murray. London: STAT Books.

Hodgson, Percival. 1958. Motion Study and Violin Bowing. Urbana: American String Teachers Association.

Books on Raymond Dart and the Alexander Technique

Skill and Poise by Raymond Dart. 1996. Includes the following writings by Raymond Dart: “Voluntary Musculature in the Human Body: The Double-Spiral Arrangement,” first published in The British Journal of Physical Medicine, December 1950, “The Significance of Skill” 1934, “An Anatomist's Tribute to F. Matthias Alexander” 1970, “The Postural Aspects of Malocclusion” 1946, “The Attainment of Poise” 1947, “Weightlessness” 1961. Also includes “The Dart Procedures” by Alexander Murray.

Beginning from the Beginning: The Growth of Understanding and Skill. A Conversation about the Dart Procedures with Joan and Alexander Murray.

Web Sites

Neuromuscular Anatomy, Child Development, and Evolution for the Alexander Technique. AT Anatomy Weebly by Alexander Murray and Anna LeGrand.

Video

The Dart Procedures /

The Dart Procedures 2 /

Demonstration of the Dart Procedures from Alex Murray's talk on the Dart Process at the Freedom to Move Conference 2014 /

The Development of the Dart Procedures: Joan Murray /

Interview with Alexander Murray on the Dart Procedures

Back to:

Alexander Technique: The Insiders’ Guide

Alexander Technique: The Insiders’ Guide

Website maintained by Marian Goldberg

Alexander Technique Center of Washington, DC

e-mail: info@alexandercenter.com

“The diagonal pull of these spirals of muscle accounts for the flexibility and upright capabilities of the human structure.” –Carol Porter McCullough