The Alexander Technique for Musicians

Applying the Alexander Technique to Modern Pedal Harp Performance and Pedagogy: A Discussion with Imogen Barford and Marie Leenhardt

by Claire Happel Ashe

“Because faulty sensory awareness caused Alexander Technique students to interpret instructions differently from the way Alexander intended them, he found that teaching through hands-on work was more effective than explaining through verbal instruction.”

(revised version from the American Harp Journal Winter 2020 issue)

|

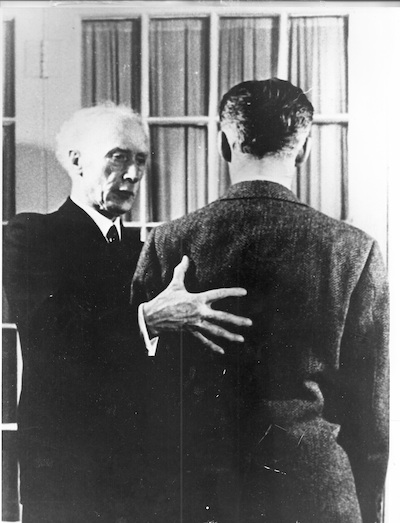

| Photo © 2010 The Society of Teachers of the Alexander Technique, London | F. M. Alexander teaching (1940s). |

In the late nineteenth century, aspiring Australian actor Frederick Matthias Alexander (1869-1955) began losing his voice during performances. Alexander sought professional medical help for the condition and was advised to rest his voice, but when he resumed speaking and performing, he again lost his ability to speak. Frustrated, he decided that he must figure out the problem for himself, and he began observing himself in a mirror. He noticed that he habitually pulled his head back every time he spoke, a habit that invariably strained his larynx. This discovery was the first step in developing what came to be known as the Alexander Technique— a method that draws on the observations he made while attempting to change this habitual pattern. The Alexander Technique uses a hands-on approach to increase awareness of how people use their bodies in activity. Alexander Technique teachers use the term poise—a state of balanced equilibrium—to describe their aim, rather than posture, which indicates rigidity or a fixed position. (1) Many performing artists in theater, dance, and music—including harpists—seek out the Alexander Technique to prevent injury, improve technique, and lessen performance anxiety; today, it is taught in music conservatories across the world. (2)

The American Harp Journal originally published two articles on the benefits of Alexander Technique by harpist Linda-Rose Hembreiker in 2010. Hembreiker presented concepts she learned as a student of the Alexander Technique that applied to both her practice and teaching. In this article, I will discuss the principles that Alexander developed and systems that have grown out of the Alexander Technique—including Body Mapping, the Dart Procedures, and the Framework for Integration—and their impact on harp performance and pedagogy. I have included the perspectives of harpists Imogen Barford, Head of Harp at the Guildhall School in London, and Marie Leenhardt, Principal Harpist of the Hallé Orchestra and Harp Instructor at Chetham’s School of Music in Manchester, England, who are both trained in the Alexander Technique. Their remarks include many insightful observations about the core principles of the Alexander Technique—principles for which Alexander coined his own terminology. These include “use affects functioning,” “psychophysical unity,” “faulty sensory awareness,” “inhibition,” “direction,” “primary control,” and “means-whereby vs. end-gaining.” Each principle is important in applying the Alexander Technique and will be addressed below.

Use Affects Functioning

When Alexander discovered that he was straining his larynx whenever he pulled his head back, he realized that use affects functioning. His own habitual patterns were causing his vocal problems. Following this principle, Alexander Technique teachers do not typically look to faulty joints or structural issues as the root of the problem and therefore do not put stock in phrases such as “I have a bad back” or “I have a bad knee”; instead they look at the way a person is using his or her body and affecting its structure in activity. Imogen Barford came to the Alexander Technique because of a repetitive use injury. “I tried everything,” she states. “I couldn’t work out what the problem was, and the Alexander Technique was the thing that unlocked it all.” Now that she has trained in the Alexander Technique, she finds that it has helped her and her students’ functioning far beyond injury prevention.

Obviously, injury prevention is a by-product [of the Alexander Technique]. [But] for me, my interest is in two things [when applying the Alexander Technique to harp performance and pedagogy]: virtuosity–enabling people to let go of things that they don't know are happening so they can have that kind of freedom which looks natural . . . The other one is the musical expression because obviously the tension will hamper that. (3)

For Barford, the Alexander Technique not only helps prevent injury but also helps increase virtuosity and musical expression at the harp by helping harpists recognize how they are interfering with their natural abilities.

Psychophysical Unity

As Alexander observed himself in a mirror, he realized that his habitual pattern began at his head and affected his balance and muscular tone all the way to his feet. He began to see that the faulty pattern was not just in his neck and throat but throughout his whole body—even the thought of speaking engaged the pattern. In order to regain his voice, he had to alter the pattern that interfered with his natural balance and poise. This adjustment led him to the principle of psychophysical unity, a concept proposing that how one thinks about an activity affects how one does it and that every action in one part of the body is supported or interfered with by the rest of the body.

For harpists, psychophysical unity influences one’s approach to technique as well as one’s general mental approach when playing and teaching. A performer’s attitude impacts the body’s muscle tone, which cannot be fully changed without observing the thought patterns that direct the performer’s playing. Marie Leenhardt finds that the Alexander Technique makes her more patient when a student does not understand something in a lesson. Moreover, she is less likely to ignore the psychological aspect of playing the instrument. When students are overwhelmed or anxious about succeeding in upcoming juries, for example, they will use their bodies more efficiently if they take a step back and notice how they are accomplishing their goals and where their attention is placed. Leenhardt explains,

If I want [students] to relax, I have to put them in a situation where they can be relaxed, not by telling them to relax . . . I say things more to distract them when I see them working too hard: think of your sitting bones, think of the space around you, think of your back, or listen out . . . The more they listen to the sound–immediately their use changes. (4)

Leenhardt is describing an environment she and other Alexander Technique teachers try to create: one in which students are given a choice beyond unconsciously engaging their habitual sense of what it is to be “right.” Alexander Technique teachers seek to help students find a state in which they are not interfering with their own coordination.

Psychophysical unity also affects harpists’ physical approach to the instrument. Imogen Barford describes her early training at the harp in relation to the Alexander Technique,

My [harp] teachers would talk about the hands and the elbows but not at all about what was supporting them–the whole . . . and [they did not talk about] how much the legs can pull you down . . . In harpists, the legs get very, very tight–particularly the insides of the legs, and we don’t take enough notice of how that can pull on the front and on the arms . . . and pull on everything. (5)

In the Alexander Technique, teachers do not change something about hand position or the relationship of the head and hips and expect it to have an isolated effect. They look at the whole, and when they look for changes in one part, they aim to affect the balance of the whole self.

Unreliable Sensory Appreciation

After discovering that the relationship of his head, neck, and back had caused his strained larynx, Alexander began trying to change his habit. But when he began to speak, he saw in the mirror that the same pattern took hold even though he could not sense himself pulling his head back. This led him to realize that what he felt was happening was not what was actually happening, and he called this phenomenon unreliable sensory appreciation, or faulty sensory awareness. Imogen Barford finds that playing in the high and low registers often causes harpists to lose their balance without being aware of it. “Even the use of the words high and low can pull [harpists] off [their] sitting bones.” (6) On the piano, high and low registers are associated with shifts side-to-side; on the harp, however, high and low registers are closer or further from the head and torso. When a harpist plays in the high register, typically the head pulls back and the chest lifts; when the harpist reaches for the low register, the body collapses down. Often this response is so habituated that the difference in posture when playing in the high and low registers is not felt kinesthetically.

Harold Taylor, author of The Pianist’s Talent: A New Approach to Piano Playing Based on the Principles of F. Matthias Alexander and Raymond Thiberge, describes Thiberge’s realization that his piano teachers’ verbal instructions differed from their actions. Thiberge, who was blind, put a hand on his teachers as they played. He wrote, “To my great astonishment, my hands revealed to me that their technical procedures were actually in disagreement with the principles they professed!” (7) Teachers also encounter faulty sensory awareness when students play a short passage in a new way following the teacher’s suggestion but then revert to their typical way when they play it in the context of the piece and cannot feel that they are reverting.

Because faulty sensory awareness caused Alexander Technique students to interpret instructions differently from the way Alexander intended them, he found that teaching through hands-on work was more effective than explaining through verbal instruction. Barford says that with her harp students, “I normally stand behind them when they are on the stool and I put my hands on their shoulders [of the student]. That’s a very common thing that I do just to get them really releasing onto the chair...and they can find balance, and they can find the sitting bones, and I can see how much they’re not on them or on them. For that, I would have hands on.” (8)

Inhibition

Alexander is often quoted as saying, “If you stop doing the wrong thing, the right thing will do itself.” (9) He found that if he tried to fix his problem by pushing his head forward or by doing exercises to strengthen his neck flexors there was no positive change in the overall pattern. Instead, it created a new habit of overcorrecting on top of the already existing one. He found that his head, neck, and back returned to a poised balance when he simply inhibited, or stopped, himself from pulling his head back. Inhibition is a principle of the Alexander Technique that distinguishes it from other methods that teach exercises or strategies to “fix” technique or posture rather than offering strategies to increase awareness of habitual behaviors. The Alexander Technique is often referred to as a method of re-education, which implies that the body is naturally balanced when one stops interfering with it.

Alexander’s use of the word inhibition relates to the definition used in physiology that contrasts with excitation but differs greatly from the definition used in psychology where it refers to the Freudian sense of repression. (10) Researcher and writer on the Alexander Technique, Frank Pierce Jones (1905-1975), explained that although “Inhibition is a negative term . . . it describes a positive process. By refusing to respond to a stimulus in a habitual way you release a set of reflexes that lengthen the body and facilitate movement. The immediate result of Alexandrian inhibition is a sense of freedom, as if a heavy garment that has been hampering all of your movements has been removed.” (11)

Inhibition in the Alexander Technique is also distinct from “relaxing.” Alexander found that the instruction to relax caused students to both lose the support of poise and to employ their mal-coordinated habits, habits that engaged in response to efforts to improve. Barford explains, “I try to use words like buoyancy and springiness and elasticity rather than relaxing. I try to use ‘feel the string’ rather than ‘press the string’ or ‘squeeze the string’ which a lot of people use, which is my least favorite.” (12)

When practicing the principle of inhibition, observation of interference becomes primary to changing one’s technique above “fixing” isolated issues. Marie Leenhardt discusses the problem of constantly correcting students to the detriment of their use. Her own training involved

. . . a lot through correcting, correcting, correcting. And it can have some good results but it can bring a lot of neuroses and [result in] never being satisfied and never feeling that you're good enough, never enjoying really because you're aiming so high, and I find that sometimes you can get in the way by not allowing [students] to develop in their own space. (13)

Alexander Technique teachers typically aim to have students discover their habits for themselves as the teacher gives them an experience outside of their habitual one. Barford explains, “We quite often have it in class where someone comes and plays . . . and it doesn’t go well, and they can see and hear how a few little inhibitory thoughts can have a massive impact on how easy it feels, how easy it looks, and how good it sounds. The quality of the sound is enormously impacted. I’ve become very interested in virtuosity, and how you can teach virtuosity by using inhibitory thoughts to remove the physical interference which blocks the sound and prevents ease, freedom, and flow.” (14)

Direction and Primary Control

|

Photo by Sara Wright. |

Author Claire Happel Ashe |

Alexander’s principle of inhibition is directly linked to his principle of direction. He found that there is a natural direction of the head upward away from the ground when poised and that the head is always balanced in relation to the neck, back, and limbs in a dynamic relationship. The purpose of Alexander Technique lessons is to help students find good direction through learning to inhibit interference with it. Direction is not a physical movement but a direction of attention. In Alexander’s own habit, he impeded the direction of his head forward and up by pulling it back and down. In order to inhibit this habit, he thought of the head going forward and up. (15) By directing himself clearly, he inhibited his habitual response of pulling the head back and down.

For harpists, the direction of the head, neck, and back, have a large impact on the use of the arms and hands at the harp. The various positions traditionally taught as correct harp hand position can be thought of as a set of constantly changing, optimal relationships between the fingers, thumb, wrist, elbow, and back, rather than a static position that must be held.

When directing the whole self, Alexander found that the relationship between the head, neck, and back was fundamental to the use of the whole. This reinforces the principles of psychophysical unity and direction but places the relationship of the head, neck, and back at the top of the hierarchy of the use of the body. Alexander found that the direction or relationship of the head, neck, and back is crucial to poise, and called it primary control.

The concentration of sensory organs at the head (eyes, ears, nose, mouth) is part of the hierarchical design of primary control in which the head and neck relationship affects the whole self and is balanced through the sensory organs. Listening is an important part of this system. Marie Leenhardt explains, “I think the listening is very important. The more [students] listen to the sound, immediately their use changes. So I try to get them away from doing, doing, doing, and more into listening and opening.” (16) By bringing attention to the sensory information in the environment aurally or visually, often the relationship of the head, neck, and back lengthens. Sensory feedback from the eyes and ears about the position of the head, neck, and back can be used to observe when one is pulling the head off balance.

Means-Whereby versus End-Gaining

Alexander found that if he solely thought about speaking, his faulty habit took hold and he was not able to sense his head pulling back. He discovered that he had to create a strategy of speaking without pulling his head back. He did not stop his habitual pattern by directly thinking of speaking or putting the head in the right position but through the indirect procedures of inhibition and direction. He described this focus on process above results as “means-whereby versus end-gaining.” Linda-Rose Hembreiker, in her article on the Alexander Technique for harpists, offers a useful definition of end-gaining: “the practice of using any means necessary to reach a goal.” (17)

End-gaining often occurs when musicians choose repertoire that is beyond their musical knowledge or technical capacity. When students play pieces beyond their coordination and skill, they may not be able to keep their attention wide on both their own use and the musical intent of the piece. Hembreiker also gives examples of end-gaining in music when harpists try to “cram” prior to performances or to play loudly without noticing the effect of that intention on their whole self. (18) Instead, through inhibiting the desire to play louder, to play a piece “perfectly,” or to play quickly at all costs, performers can observe themselves in the present, play with poise, and perform at a level commensurate with their own individual understanding and capacity.

Marie Leenhardt finds that she often applies Alexander’s means-whereby principle in teaching:

[In teaching younger beginners], I can see how the first lesson was great and then they haven't applied what I told them and I start to be too end-gaining to get that. And I can see them change–they’re less lively . . . This one [student] is full of goodwill, and I can see her not understanding what I want . . . I need to find the means-whereby, and I need to get her to slowly evolve because I realize she hasn't got it, and she needs to grow before she can do it. (19)

By inhibiting her desire to tell the student directly what is wrong (since the student is not ready to act on it) she patiently figures out the process that the student needs to gain understanding. Leenhardt also finds herself end-gaining in her own playing. She describes:

. . . when I started [Alexander Technique] lessons, the discovery was that I saw trying hard as a means to an end. And it was realizing that I was actually getting in the way so much. One of the pin-dropping moments was when I had an [Alexander Technique] lesson on the harp – [the teacher] would come to my house occasionally, and I hadn’t warmed up that day, and she worked on me for 5-10 minutes and then, not having warmed up, I started to play the passage that I found difficult. It was much easier than when I warmed up and I realize the warming up was putting on a lot of habits that were actually getting in the way. (20)

In another experience, Leenhardt found herself end-gaining with many concerts to prepare and little time. She was using the Alexander Technique in order to play the notes perfectly. When she realized that she was using it to “get it right” (i.e. end-gaining), a fellow Alexander Technique teacher suggested that she begin observing her use in an easy piece as a means-whereby to find a space where the desire to be perfect lessened. She explains, “sometimes I just play a bit of [an easy, familiar] piece and then go back to something else that I was practicing [for a concert], and it really helps a lot. I think for me that's more important than going into the details of the body.” She also finds that improvising can be a useful process to inhibit end-gaining tendencies. She states, “And improvising is the same–I'm not a great improviser–but if I feel I’m getting stuck with the harp, I’ll do a game of just making nice sounds and listening and being more into the resonance of it rather than the results side of it.” (21) Many Alexander Technique-trained musicians find improvisation to be a useful tool in which they play for enjoyment within their capacity rather than attempting to play passages that are beyond their abilities at the moment.

Leenhardt has another process or means-whereby that allows her to notice if she is interfering with her natural poise. It involves a phrase she learned from an Alexander Technique teacher-musician, and she uses it to broaden her awareness and bring attention to her balance through her sit bones before important solos and orchestral entrances. She asks herself, “Am I breathing? Am I aware of the space around me? Am I balanced?” These questions offer a chance to gain awareness and bring about change indirectly by bringing attention to various aspects of one’s use: holding one’s breath; narrowing one’s focus; or lacking balance on one’s sit-bones. Leenhardt describes her use of it in the context of orchestral playing,

It's always the moments when you have so long to wait until you play, and more and more the way I deal with it is to try not to separate what I do from the rest. So I really listen beforehand so that what I do is part of [it. And] I really listen after because I notice I overthink it, so I try not to do that and try to stay in the sound–basically [I try] to take myself out of it more and be part of the whole, and what's past is past. As soon as I finish, I keep listening to what's going on, but these three questions also really help me to be present. I think they give you a lot of presence, even in solo recitals. (22)

She finds a similar re-directing of attention useful for her students.

A student once told me: ‘Oh, those two lines, I can't do them.’ It was Pierné’s Impromptu-Caprice in the pedals bit, and I said ‘Okay, do it this time and think about your sitting bones and think about the space around your head.” She tended to clench her jaw a lot, so I did it again, and I said, “Blow a feather. Just imagine you’re blowing a feather while you play.” And she did it again, and every time I asked her [to think of] something . . . that was not about playing the notes . . . she was playing it. And she looked at me and said, ‘how do you do this?’ because she was amazed that in five minutes of this work she could play perfectly the two lines that she had been struggling to learn and felt she couldn’t play. It was a wonderful illustration of how helpful looking after the means-whereby can be. (23)

Leenhardt also describes a practice method she uses from a well-known introductory Alexander Technique book for musicians, Indirect Procedures by Pedro de Alcantara:

When something is difficult, I don’t necessarily practice it slowly, but, for instance, I repeat passages or repeat each bar so that you can sight-read it and keep going. Or I make a pause. In a 4/4 bar, you make a pause for one or two beats in which you think your [Alexander Technique] directions again and then you continue. For anything that's repetitive and tiring, to do that has really transformed it for me. In things that I struggled with for years, I did that, and it solved it. I also use that a lot with my pupils. (24)

Body Mapping

There are several systems that are used by Alexander Technique teachers and musicians which stem from the Alexander Technique. One is Barbara Conable’s Body Mapping, which seeks to provide clear and practical information about anatomy and movement for musicians. (25) Imogen Barford uses Body Mapping as an important part of teaching the Alexander Technique to her students. She feels that Body Mapping helps students have a clear idea of their structure and states, “Body Mapping is the address, and Alexander Technique is the message.” The aspects of Body Mapping that relate most to harpists from her point of view are,

. . . the structure of the hands and arms–that the forearm and hand turn at the elbow rather than the wrists. The nature of the fingers. I like to make a distinction between the parts of myself that I can have a conversation with and negotiate with, which are the soft tissue[s]—the muscles that I can talk to, as opposed to the bits that I can't talk to, which are the bones. Then I understand what I can let go of and what I can have a conversation with. And that's what I find useful about Body Mapping—[to understand that] there's not one great big mass, say ‘a shoulder,’ but that it’s made up of areas that really respond to direction, which are the muscles, and other areas that don’t, which are the bones. (26)

She also describes the shoulder joint in more detail:

So what does that joint like? The meeting of these three things they call the collar bone, the shoulder blade, and humerus . . . It's a very delicate and small affair really. . . ! It's just that little dainty joint, and everything else [around it] I can talk to and let go of . . . We can think of things like shoulders being very opaque and dense and like a big thing that tends to hold lots of tension. (27)

Dart Procedures

The Dart Procedures are a set of movements and “postures” from early childhood development that are based on the ideas and articles of neuroanatomist and anthropologist Raymond Dart (1893-1988). Dart discovered connections between the Alexander Technique and his own knowledge of anatomy and development and believed that developmental movement patterns underlie ease, balance, and poise in skill. Former London Symphony Principal Flutist Alex Murray and his wife Joan Murray (both trained in the Alexander Technique) put Dart’s movements and positions together in a sequence that progresses from fetal to crawling to standing upright and began using the patterns in their Alexander Technique teaching. Today, many Alexander Technique teachers trained under the Murrays find the Dart Procedures useful in finding coordination in movement.

Dart drew a distinction between an Alexander Technique approach to his developmental movement patterns and other approaches:

This training is not so much a training to do good movements as a restraining of the individual from performing improper and inappropriate movements by means of manipulative and personal inhibition. A sharp distinction should therefore be drawn between the inhibitional manipulative education for the body in respect of symmetry and poise [the AT] and the procedures carried out by naturopaths, chiropractors, osteopaths, bonesetters, and others who manipulate body parts on one or more occasions for the purpose of relieving pain. (28)

Thus, observation and awareness of habits is integral both to the Alexander Technique and the Dart Procedures. It is a different approach than traditional methods that teach new techniques or voluntary movement to students. The Dart Procedures always: 1) begin with the intention to see, hear, smell, taste, or touch something rather than the intention to create a position or movement (i.e. voluntary movement); 2) occur in all humans with a healthy development (e.g. fetal, crawling, creeping, walking); 3) are patterns that coordinate the whole self; and 4) involve movement and direction rather than positions.

There are developmental movement patterns that underlie harp technique. By understanding and moving through developmental movement patterns of grasping and reaching, harpists can use these procedures to find coordination and sense what is interfering with ease, strength, or facility at the instrument.

|

|

|

Framework for Integration

Another system that evolved from the Alexander Technique and the Dart Procedures is the Framework for Integration. It was developed by dance professors and Alexander Technique teachers Rebecca Nettl-Fiol and Luc Vanier as part of their efforts to apply the subtlety of the Alexander Technique to the dynamic, large-scale movements of dance. By creating a framework for understanding the patterns of the Dart Procedures, they rely less on the hands-on work of the Alexander Technique and more on guiding students through movement patterns and pointing out the nature of those patterns.

Nettl-Fiol and Vanier have found that their point of view on coordination can be applied more broadly to all skills. While some of the movements and patterns involve a large range of motion, applications to playing the harp occur at a subtler level. One application is that the fetal pattern provides a push in the limbs which aids strength in the thumbs in relation to the back. The opposing pattern of pulling forward along the floor, colloquially known as “tummy time,” creates a pull in the limbs which aids the opposing fingers in relation to the back. Both the push and pull of these patterns create a balance in the hand that provides strength and freedom in harp playing.

Because Nettl-Fiol and Vanier approach their work from a developmental point of view, they accept each student’s individual level and do not try to force a higher level of skill for which the student is not ready. As teachers, they observe students’ patterns through the framework and help students discover how they might be interfering with the underlying developmental pattern that supports the movement. Their method becomes especially useful when applying the Alexander Technique to skills that require virtuosity because when a high level of skill is needed, the direction to “think head up” may not provide the full range of tools needed to play a difficult passage.

Many musicians know intellectually that performance on their instrument involves the whole of themselves, that the use of their arms is related to their backs, and that distortion of the spine is not useful, but they lack procedures to observe themselves and change unconscious habits. The Alexander Technique, Dart Procedures, and Framework for Integration provide that.

The Alexander Technique and all systems related to it provide an alternate lens through which to see harp performance and teaching. While some students thrive under traditional instruction, the innovative systems presented in this article are intended for students who feel they could benefit from an approach that goes beyond the traditional models. Both professional and student harpists suffer many occupational hazards, from tendonitis, tightness, and joint pain to psychological stress. For all those that do, the methods discussed here might allow them to play with more freedom and ease and prevent injury.

1. Raymond Dart, “The Attainment of Poise,” in Skill and Poise, ed. Alexander Murray (London: STAT Books, 1996), 111.

2. e.g. The Juilliard School in New York City and the Royal College of Music in London.

3. Imogen Barford, online video conference with author, August 22, 2018.

4. Marie Leenhardt, online video conference with author, September 25, 2018.

5. Marie Leenhardt, online video conference with author, September 25, 2018.

6. Imogen Barford, online video conference with author, August 22, 2018.

7. Harold Taylor, The Pianist’s Talent: A New Approach to Piano Playing Based on the Principles of F. Matthias Alexander and Raymond Thiberge (London: Kahn and Averill, 2002), 36.

8. Imogen Barford, online video conference with author, August 22, 2018.

9. Judith Kleinman and Peter Buckoke, The Alexander Technique for Musicians (London: Methuen Publishing, 2014), 223.

10. Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) defined inhibition as “the expression of a restriction of an ego-function. A restriction of this kind can itself have very different causes.” Sigmund Freud, “Inhibitions, Symptoms, and Anxiety” in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. 20 (1925-1926), 75-172, quoted in Nicolas Dissez, “Inhibition,” in the International Dictionary of Psychoanalysis, ed. by Alain de Mijolla, vol. 2 (Detroit, MI: Macmillan Reference USA, 2005), 832-833.

11. Frank Pierce Jones, Freedom to Change: The Development and Science of the Alexander Technique (London: Mouritz Press, 1997), 11.

12. Imogen Barford, online video conference with author, August 22, 2018.

13. Marie Leenhardt, online video conference with author, September 25, 2018.

14. Imogen Barford, online video conference with author, August 22, 2018.

15. Alexander used the word “thought” to teach his students to direct themselves.

16. Marie Leenhardt, online video conference with author, September 25, 2018.

17. Linda-Rose Hembreiker, “Incorporating the Alexander Technique into the Daily Practice Session,” The American Harp Journal 22, no. 4 (Summer 2010): 39.

18. Hembreiker, “Incorporating,” 38.

19. Marie Leenhardt, online video conference with author, September 25, 2018.

20. Marie Leenhardt, online video conference with author, September 25, 2018.

21. Marie Leenhardt, online video conference with author, September 25, 2018.

22. Marie Leenhardt, online video conference with author, September 25, 2018.

23. Marie Leenhardt, online video conference with author, September 25, 2018.

24. Marie Leenhardt, online video conference with author, September 25, 2018.

25. William Conable, "Origins and Theory of Body Mapping," in The Third International Alexander Congress

Papers, Engelberg, Switzerland (Bondi, Australia: Direction, 1991) quoted in Jennifer

Johnson, What Every Violinist Needs to Know About the Body (Chicago: GIA Publications, Inc., 2009), 185-189

26. Imogen Barford, online video conference with author, August 22, 2018.

27. Imogen Barford, online video conference with author, August 22, 2018.

28. Raymond Dart, “The Postural Aspect of Malocclusion,” in Skill and Poise, ed. Alexander Murray (London, STAT Books, 1996), 98.

About the Author

Chicago-based harpist Claire Happel Ashe performs with ensembles throughout the Midwest including the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra, Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra, and Newberry Consort. She was a 2007-08 Fulbright Scholar under Jana Boušková in Prague and holds degrees from Yale University and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where she also received a BFA in Dance. In 2016, she completed training at the Alexander Technique Center Urbana with Joan and Aleander Murray and currently teaches harp, movement, and the Alexander Technique at the Music Institute of Chicago, Valparaiso University, Olivet Nazarene University, and in the Homewood Public Schools.

Contact the Author Claire Happel Ashe

Website: www.clairehappelashe.com

Links

- The Dart Procedures

- Neuromuscular Anatomy, Child Development, and Evolution for the Alexander Technique. AT Anatomy Weebly by Alexander Murray and Anna LeGrand.

Back to:

Top

The Alexander Technique for Musicians

Alexander Technique: The Insiders’ Guide

The Alexander Technique for Musicians

Alexander Technique: The Insiders’ Guide

Web site maintained

by Marian Goldberg

Alexander Technique Center of Washington, D.C.

e-mail: info@alexandercenter.com